The Zombie Apocalypse Is Upon Us

Part I: Zombies Become Zombies

This is the Zombie Apocalypse. This time in history, this moment in time. The Zombie Apocalypse is real, it’s happening, and it’s every bit the fevered, desperate nightmare we always hoped it would be.

I’m not sure how we escape it. The path to safety is already under our feet, if it exists, but I can’t see it to follow it. And no one’s sent me a map.

Achieving a sense of direction during the Zombie Apocalypse is clearly harder than it looks in the movies. Exactly three kinds of people run around in zombie movies – two, if you don’t count the zombies: 1. people with a sense of direction who survive for a long time, sometimes even until the end of the movie, and 2. people who run, with their arms flailing, from the fingertips of one group of leering zombies into the embrace of another group of leering zombies. Assuming we aspire to be non-flailing, it probably makes sense to stop, pant here for a second, and think things through.

I desire to be non-flailing. Let’s not flail. Personally, I’m going to calm down, have a cheap, stale cigarette that I found on the ground – like it matters at this point – and try to figure out exactly where we are.

—— We’re in the middle of the Zombie Apocalypse.

Right. Not helpful.

But, how did we get here?

As far as I can tell, we reached this madness by taking two paths through time, and here at the Zombie Apocalypse, the two paths crossed. Along the first path, the zombies became zombies — we learned what the Z-Plague would be, what to call its parts. The first path is pretty clear. We can start there.

See? Already, we’re getting somewhere. If we all stay calm, we might just survive this thing.

—– You hear something?

Zombies Become Zombies

First Taste – Yum!

Americans first learned about zombies from a travel book they read in 1929, from a play they saw in 1932 that was inspired by the travel book, and from a movie they saw in 1932 that was inspired by both the play and the travel book (directly).

First, the movie.

The movie was White Zombie, directed by Victor Halperin. It starred Bela Lugosi, Madge Bellamy, John Harron, and Robert Frazer. It’s usually described as “atmospheric,” “old-fashioned,” and bad.

Note: White Zombie has been described in the above terms, including “old-fashioned,” since it opened in 1932. The era of motion pictures with sound had begun, and White Zombie, though it had sound, was too reminiscent of a silent film for contemporaneous taste.

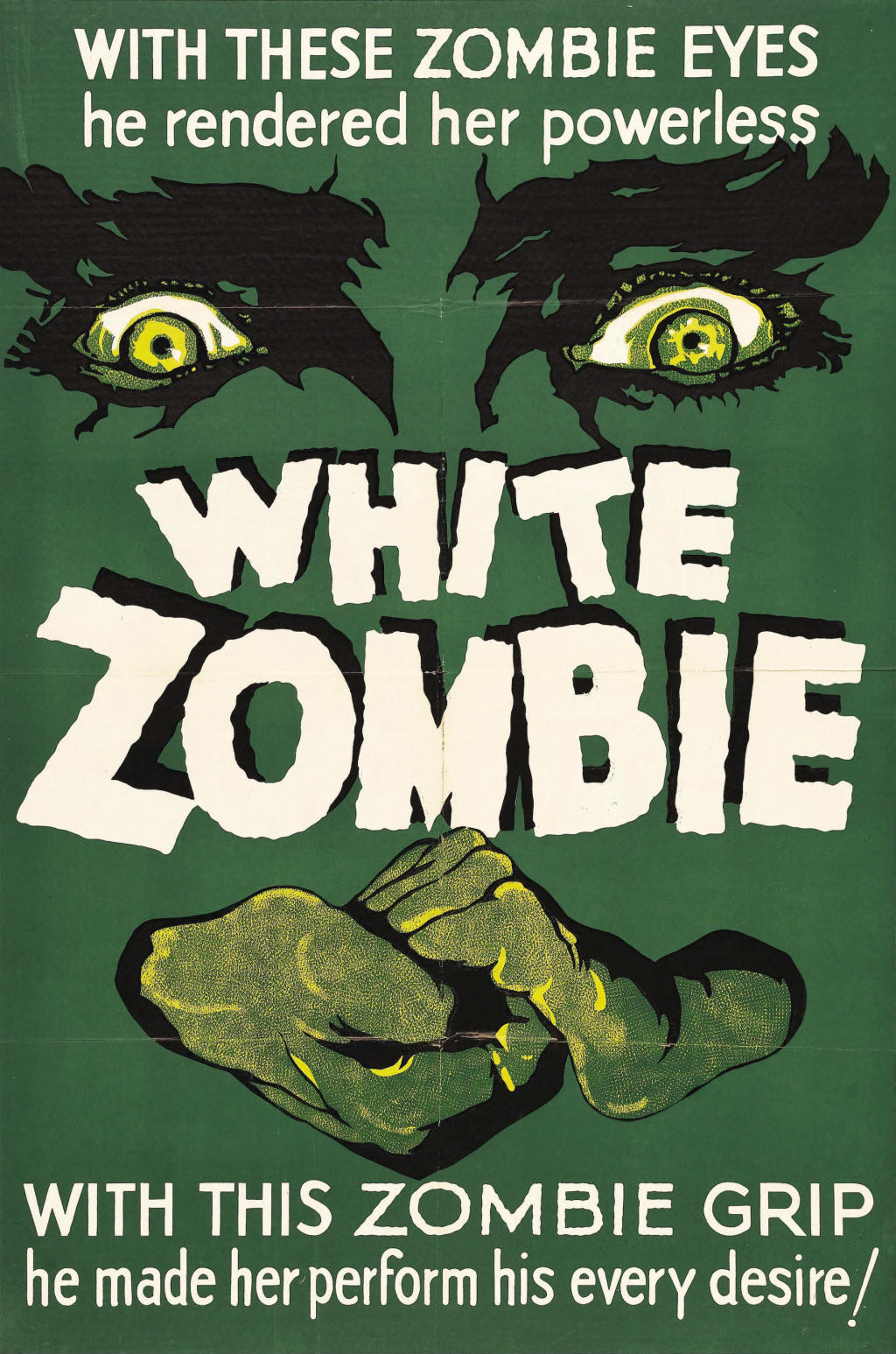

Promotional poster for White Zombie.

With these zombie eyes, he rendered her powerless. With this zombie grip, he made her perform his every desire!

Even in 1932, men dreamed of finding ways to get their girlfriends to answer email.

White Zombie opens with a bride-to-be and her fiancé riding to their wedding in a carriage that must clip-clop uncertainly through a Voodoo funeral that is taking place in the middle of the road.

I know. Subtle. But, obediently staggering along the mouldering pave-stones along which all horror story victims must stagger, our heroes can’t take a hint.

The story of White Zombie isn’t that bad, even if the movie mostly is. Madeleine Short (Bellamy) and Neil Parker (Harron) have been invited by Charles Beaumont (Frazer) to have their wedding at his opulent plantation in Haiti, neither of them knowing that Charles intends to seduce and marry Madeleine himself. To that end, Charles has enlisted the help of his wicked neighbor, the Voodoo master Murder Legendre (Lugosi). After Madeleine and Neil arrive, Murder uses his evil, witchy-man eyeball power, along with a secret potion, a candle whittled into a human likeness, and a weird, Communist hand gesture, to transform Madeleine into a zombie.

The movie is worth seeing. The brief scene of the inner workings of Murder’s mill is likely how the movie continues to earn “atmospheric,” and the scene where room-temperature Madeline plays the piano for anguished Charles is very strange and thought provoking.

White Zombie is just over an hour long.

At the moment, the movie is freely available for watching online and downloading. And since it has a coveted place in zombie lore as the first zombie movie, hordes of misinformational essays, staring creepily at the movie from different angles, are also available. For our purposes: it’s there.

So much for the movie.

To the play.

The play was Zombie, by Kenneth Webb. It was a drama in three acts, set in “the living room of a bungalow in the mountains of Haiti.” It opened on February 10, 1932, in a place called Manhattan (a section of New York City reserved for shockingly wealthy lawyers, as well as their doctors, their bankers, their clothiers, and their man and maid-servants). The play ran for twenty-one performances and was so good that no one bothered to save a copy of it.

I did find an informative review:

Mr. William Seabrook’s romantic fibs about far-off places do no one any harm, and have certainly not harmed Zombie, whose playwright (Kenneth Webb) seems to have read author Seabrook’s The Magic Island. Haitian zombies are those unfortunate people who have been resurrected from the grave and placed in peonage by villainous masters. With one of these voodooistic overlords, a family of white planters comes in contact, thus giving Zombie its motivation. For the most part wretchedly acted (including the work of Miss Pauline Starke, deep-voiced one-time film actress) and beset with deplorably written dialog, Zombie has at least four authentic shudders for your spine, to wit:

1) When the shrouded grave-folk first appear.

2) When one of them is released from half-life to total death by spell and incantation.

3) When actress Starke discovers that her husband has become a zombie.

4) When the zombies grope their way toward their master, who is in peril.

“Theatre: New Plays in Manhattan: Feb. 22, 1932”

Time Magazine

Note: For anyone that has seen the movie White Zombie, the above review for Zombie probably sounds suspiciously familiar. The creators of Zombie thought so. They sued the movie creators for copyright infringement. They lost.

So much for the play.

To the book.

The travel book, as already revealed out-of-sequence by the above big-mouthed Time reviewer, was The Magic Island, by W. B. Seabrook (William Buehler). This non-fictional book chronicled Seabrook’s experiences in Haiti. Since nothing I could write could be more interesting or on-point than Seabrook’s own account, the following is an excerpt from the chapter “. . . Dead Men Working,” the wildly seductive sixteen pages that introduced the world to the word “zombie.”

“As Polynice talked on, I reflected that these tales ran closely parallel not only with those of the negroes in Georgia and the Carolinas, but with the medieval folklore of white Europe. Werewolves, vampires, and demons were certainly no novelty. But I recalled one creature I had been hearing about in Haiti, which sounded exclusively local — the zombie.

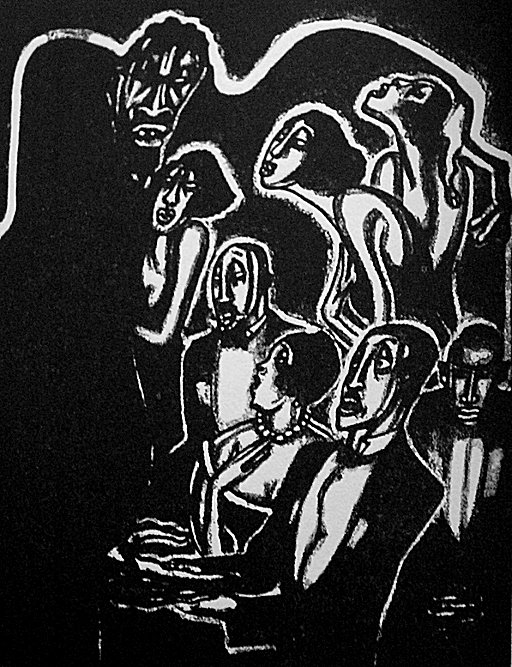

“. . . strange tales are told of Voodoo in the boudoir and salon”

Plate from The Magic Island.

“It seemed (or so I had been assured by negroes more credulous than Polynice) that while the zombie came from the grave, it was neither a ghost, nor yet a person who had been raised like Lazarus from the dead. The zombie, they say, is a soulless human corpse, still dead, but taken from the grave and endowed by sorcery with a mechanical semblance of life — it is a dead body which is made to walk and act and move as if it were alive. People who have the power to do this go to a fresh grave, dig up the body before it has had time to rot, galvanize it into movement, and then make it a servant or slave, occasionally for the commission of some crime, more often simply as a drudge around the habitation or the farm, setting it dull heavy tasks, and beating it like a dumb beast if it slackens.

“As this was revolving in my mind, I said to Polynice: ‘It seems to me that these werewolves and vampires are first cousins to those we have at home, but I have never, except in Haiti, heard of anything like zombies. Let us talk of them for a little while. I wonder if you can tell me something of this zombie superstition. I should like to get at some idea of how it originated.’

“My rational friend Polynice was deeply astonished. He leaned over and put his hand in protest on my knee.

“‘Superstition? But I assure you that this of which you now speak is not a matter of superstition. Alas, these things — and other evil practices connected with the dead — exist. They exist to an extent that you whites do not dream of, though evidences are everywhere under your eyes.

“‘Why do you suppose that even the poorest peasants, when they can, bury their dead beneath solid tombs of masonry?

“‘Why do they bury them so often in their own yards, close to the doorway?

“‘Why, so often, do you see a tomb or grave set close beside a busy road or footpath where people are always passing?

“‘It is to assure the poor unhappy dead such protection as we can.’”

“As I clambered up, Polynice was talking to the woman. She had stopped work — a big-boned, hard-faced black girl, who regarded us with surly unfriendliness. My first impression of the three supposed zombies, who continued dumbly at work, was that there was something about them unnatural and strange. They were plodding like brutes, like automatons. Without stooping down, I could not fully see their faces, which were bent expressionless over their work. Polynice touched one of them on the shoulder, motioned him to get up. Obediently, like an animal, he slowly stood erect — and what I saw then, coupled with what I had heard previously, or despite it, came as a rather sickening shock. The eyes were the worst. It was not my imagination. They were in truth like the eyes of a dead man, not blind, but staring, unfocused, unseeing. The whole face, for that matter, was bad enough. It was vacant, as though there was nothing behind it. It seemed not only expressionless, but incapable of expression. I had seen so much previously in Haiti that was outside normal experience that for the flash of a second I had a sickening, almost panicky lapse in which I thought, or rather felt, ‘Great God, maybe this stuff is really true, and if it is true, it is rather awful, for it upsets everything.’ By ‘everything’ I meant the natural fixed laws and processes on which all modern human thought and actions are based. Then suddenly I remembered — and my mind seized the memory as a man sinking in water clutches a solid plank — the face of a dog I had once seen in the histological laboratory at Columbia. Its entire front brain had been removed in an experimental operation weeks before; it moved about, it was alive, but its eyes were like the eyes I now saw staring.

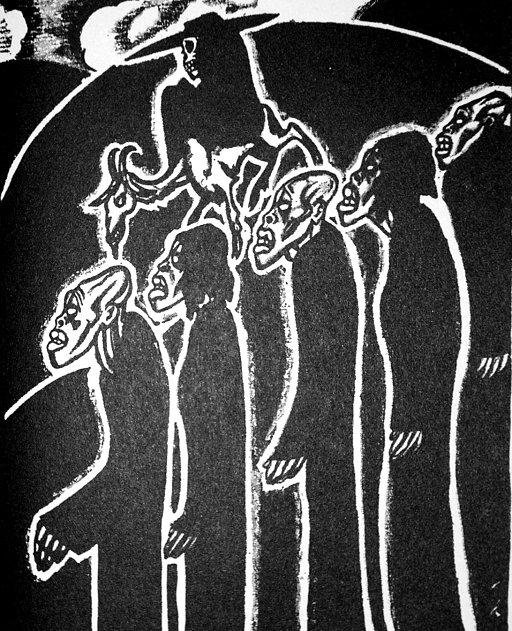

“. . . no one dared to stop them for they were corpses walking in the sunlight”

Plate from The Magic Island.

“I recovered from my mental panic. I reached out and grasped one of the dangling hands. It was calloused, solid, human. Holding it, I said, ‘Bonjour, compère.’ The zombie stared without responding. The black wench, Lamercie, who was their keeper, now more sullen than ever, pushed me away — ‘Z’affai’ nèg pas z’affai’ blanc’ (Negroes’ affairs are not for whites). But I had seen enough. ‘Keeper’ was the key to it. ‘Keeper’ was the word that had leapt naturally into my mind as she protested, and just as naturally the zombies were nothing but poor, ordinary demented human beings, idiots, forced to toil in the fields.

“It was a good rational explanation, but it was far from being the end of this story. It satisfied me then, and I said as much to Polynice as we went down the slope. At first he did not contradict me, even said doubtfully, ‘Perhaps’; but as we reached the horses, before mounting, he stopped and said, ‘Look here, I respect your distrust of what you call superstition and your desire to find out the truth, but if what you were saying now were the whole truth, how could it be that over and over again, people who have stood by and seen their own relatives buried have, sometimes soon, sometimes months or years afterward, found those relatives working as zombies, and have sometimes killed the man who held them in servitude?’

“‘Polynice,’ I said, ‘that’s just the part of it that I can’t believe. The zombies in such cases may have resembled the dead persons, or even been “doubles” — you know what doubles are, how two people resemble each other to a startling degree. But it is a fixed rule of reasoning in America that we will never accept the possibility of a thing’s being “supernatural” so long as any natural explanation, even far-fetched, seems adequate.’

�